This is a series of annual special reports for CMD from guest contributor Alex Carlin about his observations at the United Nations climate conference. — CMD Editors

#6: Final Words And A Postscript

Professor Paul Beckwith interviewing Alex Carlin at COP29. Photo by Climate Emergency Forum.

At COP29 Professor Paul Beckwith, a climate systems scientist at the University of Ottawa’s Paleoclimatology Laboratory, interviewed me for the Climate Emergency Forum. One of his comments encapsulated a very positive touchstone of the United Nations COP crusade, which aims to solve the problems arising from too much CO2 in our atmosphere:

Paul: “Alex, you’re going to like this conference because I’ve noticed a big shift. Now there is a lot more talk about OPR (ocean pasture restoration), carbon dioxide removal, OCDR (ocean carbon dioxide removal). People are getting worried. They think emissions reduction is not going to be enough.”

This new paradigm of CO2 removal is indeed gaining traction, and I believe that by the sheer force of its far superior logic it will inevitably supplant the old, failing paradigm of primarily focusing on emissions reduction. We might well look back on COP29 and mark it as the moment when we at last turned the corner with this absolutely crucial transition.

Why is this so crucial? Imagine a doctor in a hospital emergency room where a patient wheeled in on a gurney is about to die from an overdose of a poisonous substance. In this analogy the patient is our ecosystem, the poison is the excess CO2 in the atmosphere, and the doctor represents the climate movement. In the new paradigm, the doctor focuses on getting the poison out of the patient’s system as quickly as possible.

But in the old paradigm, the doctor ignores the poison and instead focuses on reducing the amount of poison the patient will ingest in the future, even though the patient will die in the meantime.

One reason it is better to focus on the existing poison is that the future poison is tiny in comparison — emissions only add 1% per year to the CO2 overdose. Coupled with the fact that today’s lethal dose of CO2 in the atmosphere takes a thousand years to go away by itself, ergo, ipso facto, we must, and we can, actively remove it rather than be unduly distracted by a future CO2 issue, which is clearly less urgent.

Postscript

Burning under the surface at COP29 was an issue that I only learned about after I had left. Armenians claim that they have been brutally victimized by the powers that be in neighboring Azerbaijan (the COP29 host country), including through ethnic cleansing in 2023. As a precondition for participation in COP29, Armenia requested at minimum that Azerbaijan free 23 Armenian political prisoners currently being held right there in the capital Baku, the site of the UN conference.

Azatutyun, an Armenian news service, reported:

“Something had to take place so that Armenia could participate,” said Sargis Khandanian, the chairman of the Armenian parliament committee on foreign relations. “And given that Armenian prisoners are being held in Baku, it is logical that Armenia and Azerbaijan should have achieved some result on this issue, that Azerbaijan should have freed and repatriated prisoners. But that didn’t happen.“

As a result, Armenia boycotted COP29 and tried to draw attention to the issue. Sadly, virtually every country and NGO participating in the conference failed to speak out about it. The silence was so deafening I did not hear one word of it until the American news organization DemocracyNow! produced an excellent segment on November 25, three days after the close of COP29. I recommend that people read or watch that report, disseminate it, do further research on this serious subject with its deep historical roots, and then devise and support ways to bring these ancient neighbors to an acceptable modus vivendi.

#5: Fair Data

Alexandra Korcheva, a scientific researcher and communicator. Photo by Alex Carlin.

Alexandra: My name is Alexandra Korcheva. I’m from Bulgaria. I am a science communicator working in Pensoft Publishers, an independent scientific publishing company. I’m also a social scientist in the field of environmental economics.

Alex: Excellent. I understand that you offer some kind of service that allows people in the climate movement to access the information they need in a better, more accurate, and more useful way. It involves open access, and various ways of facilitating access to the important information that we all need.

AK: We are big supporters of the idea of “FAIR data” and open science.

AC: FAIR data?

AK: Yes, FAIR data, [two] beautiful word[s]. “FAIR” stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable.

AC: It’s an acronym.

AK: Yes. FAIR data principles have been around for quite some time now, and they unite researchers around the idea that the data we are using for research should be open and available to all researchers. Moreover, that data should be alignable with the digital tools underpinning their scientific work, including the AI-powered technology integrated throughout the research practices of tomorrow.

For scientists to be able to create responsible and future-proof work, they need to ensure the quality of their research data so that it can be discovered and retrieved by computer algorithms, but also — and this is especially important in an AI-dominated reality — understood, interpreted, and integrated into future scientific work that builds on what they are doing today. The thing is that researchers collect so much data that hugely differs in type and dimension. Yet, to ensure the usability — hence efficiency — of those data over time, all those data resources need to be able to “communicate” with each other and build on each other’s value and meaning. Otherwise, we may end up endlessly repeating what others have done in the past rather than picking up from where they left off.

What’s even more concerning is that we might not be able to access those same sources of information any longer. Due to worldwide habitat degradation and biodiversity loss, for example, you will not find the same flora and fauna that were there in almost any habitat some 50 years ago.

AC: Yes.

AK: You collect data from various places, and generate a research outcome from your subsequent analyses. You have research teams doing that. Suppose they measure, for example, the salinity of the sea, the temperature, the diversity of species, and so on. And if these teams collect that data in a similar way, if they measure the same things with the same methodology, then they can combine these observations and use them for a comparative study. They can make the datasets public for other researchers to be able to use them as well. It would be great if they also made the data public — along with information about its collection — in a format that can be used by other researchers as well as sophisticated computer algorithms. Because of this, other researchers can later benefit from this data. And this is part of the idea that the data should be synchronized so that it can be interoperable.

AC: Why wouldn’t that happen anyway? How is your system different from the way things were before? How is it innovative?

AK: The innovation of FAIR data — which is not [exclusive to Pensoft but rather is] a global movement — is for data that has been collected not to stay private or in a format that is unusable by a large majority of researchers, but to be made publicly available to researchers in a way that they can actually use. Together with making research results open-access, this is an important element of contemporary research. There are also examples of promoting open science through grant research.

AC: Do you mean requiring certain researchers to use open-access if they want to secure a grant?

AK: I’ll give you an example. The European Union has these really big programs for funding research. The largest current program is called Horizon Europe. Researchers funded through Horizon Europe have to comply with the principle of FAIR data. They also must publish their results in open-access research articles, [which makes it] available to everybody for free, and people do not have to pay to access [this information].

Open-access research and FAIR data are part of the larger movement for open science.

AC: Can you give me an example where there’s a tendency for data to be kept private or sold or not made openly available?

AK: Oh, there are thousands of examples really — either data is private, or it is not easy to find, or it is in a format that cannot be reused. For example, it is perfectly commonplace for governments or businesses to store data which is not available to the public or is not free of charge. Another example is data [that has been] stored long-term — from 50, 60, 70, or more years back — [and] is available in formats that make it practically impossible to use. For example, it might be stored in paper format somewhere in a basement — so even if it is open to whoever needs it, it is practically impossible to use. Surprisingly, scanned documents stored on flash drives are not much different.

AC: How would your system help climate scientists find better solutions?

AK: [Climate scientists] cannot reach conclusions if they don’t have enough data or access to high-quality research. If you don’t have access to previous research and/or essential data, your own research is limited. If you… don’t know what other researchers have found out before you, you cannot do the research to prove your theory or to prove that you’re right or wrong.

Opening up research results and making collected data FAIR actually accelerates finding the truth. And for me, opening up science and making it accessible to people, making it accessible to other researchers and also communicating [the information] is … really crucial because it also demystifies science.

Science is not a mystery. Science is concrete. And when it is [practiced openly], you can see what analysis [has] actually [been] done and can check every result.

So, if a scientific article is telling you that CO2 emission reduction is the only important aspect of environmental policy, if you have open science, if you have open data, you can check the methodology, you can check what datasets this research has used, and you can check the statistical methods applied. Then, if you are enthusiastic enough, you can even rerun the underlying experiment and see for yourself whether the calculations are correct, because human errors happen too.

AC: Right.

AK: When you have open science and… the entire research process [is] open, you can see from end to end how the research team has actually done its research and has reached its conclusion. You can then also see what the weaknesses are, because each scientific study has its limitations and areas left for future improvement. You know, at the end of the day, science is not perfect. It’s modeling the world, but it is not the actual world. For example, there are always the so-called ceteris paribus conditions in research.

AC: Oh, that’s Latin.

AK: Yeah, it’s Latin. It means “all other things excluded.” So, maybe I’m investigating some factors and there can also be confounding variables that are not being investigated but may be also important to the phenomenon I’m investigating. When you have open science, you can see what the model is, what the variables are, what data is used, and what methods are applied for analyzing it. You can then know whether any gaps in the research are present — for example, whether or not the research team has missed taking into account an important variable.

AC: So, are you offering a bunch of bullet points to think about? Are you offering some software? What are you guys actually offering?

AK: We’re an independent, globally operating company that publishes open-access scientific journals in line with the best industry practices. At Pensoft, we have pledged to make sure that scientific work published in the scholarly journals we are responsible for… is here to stay…, and in very useful condition. For example, we publish not only classic scientific articles, but also datasets that can be reused by other researchers. We publish technical reports that otherwise would be lost as “grey literature.” We also publish tiny bits of scientific information about single facts, the so-called “nanopublications.” We are quite innovative, really.

AC: Would these works be considered peer-reviewed?

AK: Peer-reviewed, exactly. All research articles published by Pensoft comply with the best editorial standards, which means that they are only published in these journals if they pass rigorous evaluation by other experts in the field.

AC: How many journals do you publish? One for each subject?

AK: Currently Pensoft publishes over 70 open-access, peer-reviewed scholarly journals covering a diverse range of fields, including medical sciences and interdisciplinary research. Still, the majority — the publications we are best known for — are journals dedicated to various aspects of environmental and biological science, such as biodiversity and ecology.

Apart from a growing open-access journal portfolio and involvement in project consortia, Pensoft is known for its publishing of scientific books and conference materials. The company also maintains an in-house technological department, which is continuously working on the development of platforms and tools meant to streamline and optimize the publication and reusability of FAIR data in science. You are welcome to visit Pensoft’s website (pensoft.net) to find more about us and our activities.

AC: Let’s say Ghana is about to do a plankton restoration operation. If you become aware of that and they are aware of you and communication starts up, what do you tell them to do differently than they would without you?

AK: I tell their science officer to open up their research as early as possible, ideally by publishing both the collected data and the research work completed. An easy way to do this early on is by publishing a data paper. This is a specialized scientific article format, which is basically a method to make a dataset permanently available by means of a formal scientific publication. But also, use narrative to describe the data, including the collection methods and the context of your research work.

So, for example, those scientists working in Ghana will start by collecting their data; then they will pour all that information into a .csv file; and finally we encourage them to publish it as a data paper, so that they open up their collected data, along with all the context and information about their work necessary for others to fully grasp what they have, verify it if they wish to do so, and, in turn, use it in their own research. What’s more, since the authors of those data and the data paper itself have produced a formal scientific publication, whoever reuses their work in the future will have to likewise formally credit them, thereby acknowledging their contribution to science over and over again.

As our team has always recognized the immense value of scientific data that is readily available to anyone who needs it, Pensoft launched the Biodiversity Data Journal in 2013 with the goal of providing an extensive suite of workflows and integrated tools to make it easier for researchers to provide easy access to ready-to-reuse scientific data. One of these workflows was the data paper format, which our journal piloted in the field of biodiversity science.

AC: You would recommend that, suggest it.

AK: I would suggest that researchers who gather high-quality research data publish it as a separate data paper. As a formal scientific publication, it gets a DOI: a Digital Object Identifier. That’s the thing that identifies an item on the internet and ensures that it will remain online even if the original website where the publication is stored [no longer exists].

AC: To be more available to people searching in a more general way.

AK: Yes, DOIs are incredibly important for making publications findable.

AC: It would make a new concept like the plankton climate solution more well known around the world. This is really interesting.

AK: Yes, because if they publish their data and their research in the form of an open-access research article, then they make this science available to a wide spectrum of stakeholders — other researchers, journalists, and even policymakers.

AC: These plankton restoration companies are called “OPR” for “ocean pasture restoration.” For example, OPR Ghana, OPR Côte d’Ivoire, OPR Alaska, wherever it’s happening. Each one would have a science officer in communication with you, so that as the data comes in it would get around much faster to everybody, and this extra speed can make a critical difference.

AK: The more transparent they are with knowledge, the more the knowledge will grow.

AC: And for the plankton solution to be well known in the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] scientist community, the Biodiversity Data Journal is the one that would be most likely to catch their attention.

AK: Not necessarily. Of course, you need good research to get the attention of the expert and scientific community, but through open-access journals and showcasing the entire research process transparently — including the data collected, where journals like Biodiversity Data come in — researchers can showcase the quality of their research more effectively and get the attention of relevant stakeholders.

AC: Which analysis journal would you recommend to make a concept most available to the IPCC scientist community?

AK: It is part of the job of IPCC experts and experts in the field to be aware of good science regardless of where it has been published. However, nowadays, with the deluge of data and research publications, it is becoming increasingly harder to get the research that you need. This is why Pensoft is not only investing in future-proofing publication formats and workflows and encouraging researchers to use those, but also in aiding the better discoverability of research once it is published. One way we do this at Pensoft is to automatically export the full articles to as many scientific databases and discovery platforms used by researchers and relevant stakeholders [as possible] as soon as they are published.

AC: You’re making it easier.

AK: I hope that the idea of having more high-quality open science becomes even more popular.

AC: Do you have any further advice you want to give?

AK: Yes, I do. It is a piece of advice for researchers. We live in a world where there is too much information already available [but it’s not always clearly explained]. So even if you [practice] open science, you also have to be able to communicate it. As researchers, we are usually pretty introverted, and we often tend not to express the brilliance of our results. But good research results have to be communicated so that we can maximize the benefits to society! That’s where science communication comes in.

AC: Communication to whom?

AK: To different people, including to the general public. People are interested in science, and science can be interesting to people. For example, we have had species named after Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley published in our journals, specifically our journal in zoology systematics, ZooKeys, and this has [attracted] interest among the general public. Science communication is really important because it not only makes the science more visible, but also helps the different audiences learn new things and be informed about exciting and important scientific developments.

AC: Very good. And finally, what can you suggest to improve the current detrimental situation we have at every COP? IPCC scientists on whom the COP delegates depend for the factual basis for their action are maintaining that the main goal for COP should be emissions reduction (ER). But ER only addresses a 1% annual future addition to today’s already lethal greenhouse blanket. Therefore, a priori, ER should not be the flagship goal of COP. How can FAIR help IPCC scientists shift their priority to the far more logical goal of CO2 removal?

Alexandra referred this question to Boris Baron, her colleague at Pensoft. He told me this:

Boris: By making it clear in scientific and common sense terms that our best available tool in [combatting] dangerous climate change is the capacity of Earth’s ecosystems to absorb CO2. They have been doing this for nearly 5 billion years. What we must ensure is that we protect and restore ecosystems that we as a species have been steadily diminishing in the past 200 to 10,000 years.

Boris Barov of Pensoft Publishers. Side event at the Bulgarian pavilion at COP29 titled “Supporting Climate and Biodiversity Policy Through Open Science and Science Communication,” November 21, 2024. Photo by Pensoft.

#4: Climate and Conflict — It is Related

Nagmeldin Daoud, a Sudanese climate activist. Photo by Alex Carlin.

N: I am Nagmeldin Daoud. I’m a Sudanese climate change activist and a member of the Sudanese Youth Network (SYN). I’m also a climate researcher and an environmental researcher. I work on green finance policy specifically. I’m very happy to be here at COP 29 because I’m meeting many people from different areas, different countries, different cultures, and different backgrounds. I am making a call to all the international actors who care about peace. I am calling on them to take action.

A: You are inspiring them. You’re pushing them to action.

N: Yes — to take action to save lives in Sudan so the parties that are fighting [there will choose] peace.

A: This is about the war in Sudan. You are pushing them to stop killing each other, to stop killing civilians. Is climate connected to the conflict?

N: Yes, it is related.

A: Please explain.

N: Climate change is a significant factor in the Sudan conflict, a war rooted in complex historical, political, and social factors. Climate change has led to more frequent and severe droughts and floods in Sudan, greatly exacerbating the scarcity of resources, especially… water… and arable land. This intensifies competition for scarce resources — particularly in rural areas in the Darfour region [in west Sudan] — leading to intercommunal and interethnic conflicts. All of this leads to migration and displacement, forcing people to seek refuge in vulnerable areas [like] Darfur. As the ongoing climate crisis exacerbates political and socioeconomic factors and the underlying tensions and vulnerabilities, it contributes to the war. So, that is why I am calling for “climate action for peace” in Sudan.

A: You are pushing climate action so that there will be more natural resources and less war.

N: Yes. In Sudan the conflict started from the competition among local communities and parties for [access to] natural resources. But governments and politicians are making it much worse with their competition for resources and power, and they’re pushing civilians to kill each other.

A: You are looking at the big picture, the long run, yes? Maybe it won’t happen so quickly, but if you can deal with climate problems over the next 20 or 30 years there will be less war. Is that what you mean?

N: Right. It wouldn’t happen quickly, but yes in the long term.

A: Is there any practical reality to the idea that the warring parties in Sudan might say, “instead of killing each other let’s fight this climate problem together.” Is that a dream? Is that a total fantasy, too romantic?

N: No, it is possible. Yes, we have to unite together. We have to be united, united together to fight climate change. This is best for us. Climate change is killing us and we are killing each other. We don’t need to be killing each other, so let’s talk. Climate action can play a key role in uniting Sudanese civilians to pressure the two parties to the war in Sudan to stop fighting and start the reconstruction because climate action is for the benefit of all Sudanese people of all generations, unlike war and conflict, which destroys Sudan and the future of all generations.

A: Is there a specific climate action that you want the warring parties to cooperate on? Instead of continuing to fight each other?

N: We are pushing them to build sustainable infrastructure for food security for all in Sudan. This sustainable infrastructure has benefits for both food security and for adapting to climate loss and damage.

A: Excellent. Let’s then talk about a climate solution that is so effective it can stop a war because it can actually stop climate loss and damage. Essentially, it’s the restoration of ocean plankton, which then removes CO2 by photosynthesis. With 100 such ocean pasture restoration (OPR) actions around the world, so much CO2 is removed that the climate becomes safe again by 2050. It was done with great success near Alaska in 2012, and last year the Alaskan government held hearings on proceeding with OPR. Are you interested in learning more about the potential of plankton to solve Sudan’s loss and damage?

N: Yes! I will research more about the plankton solution.

A: Can you clarify something you said to me earlier today about the conflict between Sudanese agriculture and livestock groups. How is the government exploiting that?

N: The government has been giving guns to [members of agricultural groups] to kill [people in the livestock groups] and take their land. That was the action that [forced members of the livestock groups] to form their own army to defend themselves. But the war in Sudan is not really between two parties inside Sudan. No, it is a regional competition between countries outside Sudan.

A: You mean it is a proxy war?

N: Each faction has support from different nations. They bring them guns. Egypt is supporting one side. And the EU is supporting another side. It’s a regional war. The war in Sudan is a war between multiple internal and external parties competing for power in the country. There is a lot of evidence proving the involvement of the United Arab Emirates, the Arab Republic of Egypt, and a number of other countries in the region supporting both parties with weapons, resources, and military technology. They must stop doing this because the Sudanese need support to recover and adapt to climate change and do not need more killing.

A: Climate change created the casus belli: scarcity of resources. And you’re looking to reduce the scarcity.

N: [We face a future where] there is no Sudan. There will be no country if they continue to kill people.

Khartoum (capital of Sudan) after the fighting 2023 to 2024. Photo by Sudan War Monitor.

A: How fast could this happen?

N: In five to 10 years there will be no one. There will be no Sudan if we don’t do something because according to UNICEF now there are 25 million people suffering from hunger in Sudan, [from a] total population of… 42 million. The climate vulnerability [is severe]. Floods have destroyed more than 28 rural areas in Sudan. And I am making a call for humanitarian aid in Sudan because of this hunger and food insecurity. Many people are dying from hunger. We need humanitarian aid from the international community.

A: Here at COP29 you are pursuing humanitarian aid for those who are dying in Sudan.

N: Right, absolutely.

A: Can you tell me some specific steps where you’re making progress?

N: Yeah, there’s progress. Both parties opened the border to allow humanitarian aid [into] Sudan.

A: Did they open the border because of something you did at COP?

N: No, no. Progress about the borders was made before COP. We are now calling on all humanitarian organizations like the UN World Food Program to raise that humanitarian aid.

A: What have you accomplished here at the COP in this regard?

N: There has been a good response from international organizations to [increase] humanitarian aid and deliver [it] through the newly opened borders.

A: Can you name an organization here that agreed to raise the aid because of your efforts?

N: The International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) promised us to push the African community. This is something going on here at COP29. This COP is very focused on climate finance for exactly this [type of action]. That’s what they’re trying to make progress on.

A: You go to the meetings? Or how do you make this progress?

N: By talking to delegates, talking to people in government, in international organizations, and in the civil societies. I am also researching, talking to universities. I am making solidarity with the Sudanese people. And youth solidarity — specifically with the youth of the global south.

A: I understand you cannot live in Sudan right now.

N: Right now I live in Nairobi, Kenya because I am a refugee, displaced. It’s too dangerous in Sudan now. There is no safety for me to [be able to work there]. I would be targeted personally. [I have been] put in jail [a few times]. The regime doesn’t like activities like mine — people talking about freedom, talking about human rights, talking about saving lives.

#3: Article 6 and Climate Priorities

Ingmar Rentzhog. Photo provided by wedonthavetime.org.

The constantly scrolling list of events on the omnipresent plasma screens here at COP29 are full of meetings to work on various aspects of Article 6, a crucial piece of the Paris Agreement. Article 6 mostly lays out how rich countries can legitimately meet their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) by buying carbon offsets from poor countries working to reduce carbon. An example would be if a poor country needed that financing to restore its ocean plankton, and it certified that the resulting photosynthesis removed a certain amount of CO2 from the atmosphere, the certification would then generate carbon credits that could be sold to a rich country. The world would benefit from CO2 removal that otherwise wouldn’t have happened.

I had an opportunity to meet Ingmar Rentzhog, an uber-climate-influencer from Sweden, to discuss Article 6 and how to balance priorities between CO2 removal, methane reduction, and emissions reduction.

Ingmar: My name is Ingmar Rentzhog. I am the founder and CEO of We Don’t Have Time. We are the largest media platform for climate action. We have a 200 million monthly reach on social media, and on average 10 million viewers of our broadcasts. We are all about climate solutions.

Alex: Terrific.

I: I came up with the idea. It was the night Donald Trump won the election the first time.

A; Yes, I was in Morocco at COP21 and the entire US delegation — the Obama delegation — was in tears.

I: That was eight years ago. And actually, Trump helped me realize that our world leaders will never solve the climate crisis for us. We needed to take the leadership in our own hands.

My background is not in climate activism or the environment or anything like that. I used to work in the finance industry. I was a founder of one of the largest investor relation firms in the Nordic countries. But when I became a father, I started to read about the climate, and I became so shocked that people are not acting. I wanted to contribute. So what’s missing? We have the solutions and enough knowledge about the problems, but we need more people to be mobilized.

A: I have to stop you right there because a running thread in my journalism is challenging people who say, “we have the solutions.” Are you buying into the equation that “emissions reduction equals climate solution?”

I: I think we need all the solutions on the table.

A: Okay, but if you had a magic wand and shazam: no more cars, no more airplanes, no more oil companies, no more emissions, we would remain essentially where we are now in terms of the crisis because the lethal overdose of CO2 currently in the atmosphere takes a thousand years to go away by itself. It’s going to be too hot to work outside in Africa and in the Global South. It’s going to be too hot for farms to properly produce food. And there is going to be too much acid in the water for fish to survive. That’s with the amount of CO2 we have right now.

I: I think that we have triggered some things, but we are not over the (major) tipping points yet. We can say it like this: if we don’t really change course we are going to hit those tipping points.

A: Okay, but would you hold your breath for serious emission reductions? Emissions are still going up, not even plateauing.

I: I’m actually very convinced that we are on track to decarbonize the whole society, not by stopping to drive cars, but by changing the energy, the power sources.

A: But in any scenario, we must remove the existing CO2. Do you agree with that?

I: Yes, but you also need to do a lot more.

A: But it’s important to prioritize. Logically, the priority would be to take out the trillion tons that are currently killing us, versus the mere 1% in emissions that is added to the problem annually. If you want to guarantee a healthy future for a 10-year-old kid, your priority would be the 99 versus the one, right? The 1% would be important, but it wouldn’t be your priority. Yet here at COP that 1% is the priority, and the 99% is marginalized. For example, the secretary general of the UN likes to say ‘the one and only solution is emissions reduction.’ That’s the mantra.

I: Yes, but you need to work on the short-, medium-, and long-term [goals]. The main point here is that we need to win the marathon. The marathon is the decarbonization of society. We need to build a society that is at peace with nature. That’s the first priority. If you’re going to win a marathon, you need to be able to run a very long time. A marathon is a long [distance].

A: Well, today’s CO2 is going to cripple your marathon runner right away. That person won’t have time to even think about running, especially when he or she is dead. Your “short term” should be the priority.

I: No, no, no. If you let me finish, you will find that I’m not disagreeing with you. So, we need to win the marathon, but we also need to sprint, which is taking out the existing CO2.

A: Absolutely.

I: And you can do other stuff to cool the planet. I’m not talking about crazy geoengineering because that will create a lot of risk, and we don’t really have the political will and the technology to do it at scale. I don’t think that is something we should do here and now. So what can we do? We can do two things. It’s not only about carbon. If you really want to win the sprint, you need to look at all the greenhouse gasses. Look at the short-lived climate gasses, like methane, water vapor, black soot. There’s a big difference there because if you stop emitting those emissions, you don’t need to remove them.

A: Right, because they’re short-lived. They fall to the ground relatively quickly.

I: Exactly. They will dissolve by themselves. If we stop emitting short-lived climate gasses, we can cool the planet up to 0.5 degrees.

A: Agreed. And regarding methane and flaring from oil installations, there is a new company called CIP, Carbon Investment Partners. They use methane-consuming bacteria — also known as methanotrophs — to absorb the methane from flaring. And!! Rather than converting the methane to CO2 as in flaring, you don’t create any CO2 at all! It just creates good things that you can use for food, proteins, and biodegradable plastics. Have you heard of this?

I: That sounds great! Regarding CO2 removal, if we can find a way to do it fast, we should highly prioritize that. But we should also prioritize stopping the short-lived climate gasses, and we should continue with everything else to win the marathon. [We also need to consider] what gives us hope. I give speeches in big conference rooms like this [and] was on a panel the other day here at COP. Lately I have started to ask this question to the audience because I’m kind of fed up with the way people talk about things that are very hard to achieve but nevertheless must be achieved. My question goes like this: “According to science, we need to reduce emissions by one half by 2030. Can we do it?” I asked it just the other day in a room full of 100 high-level people here at COP, and only two people raised their hands. Only two people out of 100 believe it is possible. People are saying that we must have this mission without believing it is possible.

A: They’re just collecting a paycheck?

I: Well, we need to do what’s possible here and now, not only because we need to do it, but also because we need to get people to believe that we can do it. If you’re in a race you don’t think you can win, you will not win it.

A: I think the more you do research on ocean restoration and plankton restoration, you’re going to get excited about it being the next big thing in “doability.”

I: For your readers, I really would like to push for our campaign that I think you’re in line with. It’s not focusing on plankton (although I would love to know more), but it’s kind of the same narrative. It’s called “buy more time.” If you go to wedonthavetime.org/buymoretime, it’s all about getting [our] priorities straight to focus on what we can do fast.

A: Excellent! Now, Article 6.

I: Article 6 is all about how to get working rules for the carbon market.

A: Which rules are not set?

I: There are no global standards for it.

A: What are the issues?

I: One is [if you are a polluter] and you pay money for carbon offset credits, how can you match that to your emissions? Can you take the offsets? Are there limits? And how are you supposed to know [if] the carbon offset [project] works and is not just [existing] on paper.

A: There are companies that claim to be the arbiters of that — that determine the validity of any offsets.

I: And today there are a lot of different standards. The problem with voluntary standards is that everyone has their own rules. Some are working, some are scams, some are “working” but don’t actually work because it’s hard — you plant the forest and the forest [burns] down.

A: Please explain the difference between the voluntary market and the Paris Agreement market.

I: In the voluntary market a buyer and a seller agree on how to remove some CO2. But if there is a legal agreement [as stipulated in the Paris Agreement] it will have [a legally binding impact] on how you do it. It will create a much more stable market. [As it is] now, it’s not a legal thing.

A: They just have a handshake.

I: Yeah. So what we are trying to do here at COP is agree on how to do this with an official rule book.

A: The voluntary market doesn’t care much about what’s going on at COP29, right? They make handshake deals and the polluter gets to say “we have ESG, no problem. We’re doing it.” They get to do their PR and it has nothing to do with their NDCs or any of that.

I: Exactly. So that’s the voluntary market. That’s fine. It takes care of itself. But here they’re talking about another thing, which is related to [asking] every nation [to make] a commitment to decarbonize and then fulfill their commitments [through] the NDCs. And they can help another country by buying credits on the carbon market.

A: OK, so you’re in Sweden and your country has a problem with how much CO2 its putting out in the atmosphere. It needs to offset that to meet its NDCs. So Sweden gives some money to Ghana to create a solar plant, and that creates carbon credits that Sweden uses to offset some of its emissions. So while Sweden is not reducing its carbon footprint internally, it has done a good thing globally because Ghana just made a big move towards clean energy that it wouldn’t have done otherwise. So what is the debate here at COP29 related to this?

I: I’m not one of the climate negotiators, but as I understand it, it’s about how it should be measured. They need to standardize how they certify the amount of CO2 being removed. But it is also about justice in the sense that maybe rich countries shouldn’t be allowed to keep [endlessly] polluting by paying poor countries. So they need to standardize [whether rich countries] can do as much offsetting as they want or [be limited to] only a certain percentage of [the amount] they want.

A: Let’s assume Trump pulls out of the Paris Agreement again. How does that affect what we’ve just been talking about? Would it affect Sweden trying to do an offset deal in Ghana?

Photo provided by wedonthavetime.org.

I: I don’t think so. It’s nothing to worry about. This COP is happening just one week after the US election, and it has been quite obvious things will just continue moving on. We have also seen Argentina going home and that’s one less problem to take care of. We don’t want naysayers in the negotiating room. But the United States of America is the home of the capitalist world, right? They don’t want to miss out on a market.

And regardless of Trump, you have cities, you have states, you have a lot of businesses and local governors who want to fix the climate, and they want to make money by doing it. The US is not relevant on the world stage with Donald Trump as president. People can’t trust him. And I’m not just talking about Europe. I’m talking about the whole world. I mean, they don’t see him as a reliable partner. The world has moved on.

And I read something interesting that there was this US oil company that actually advocated for the US to stay in the Paris Agreement. Why? Because they know that if the US is not in the agreement, the world will probably phase out fossil fuel faster compared to having the US in the agreement. It’s a stupid [move] to leave the negotiations that will control the rules of the future on how this planet will work.

And Donald Trump has done one thing very good for the climate movement. He has constantly reminded everyone that we’re living in a crisis. With Trump as a president, you are always in crisis mode with tweet communication, crazy things happening. Engagement from the climate community in business and in civil society was growing momentum the same day Trump won the US election in 2016. People got motivated. And when Biden won the US election they got relaxed. We can’t have a relaxed climate movement.

A: And you are saying that there’s no free lunch for Trump by getting out.

I: Yeah, exactly. I mean, I think the country that will be damaged the most by leaving the Paris Agreement will be the United States if they leave.

A: If the US is outside the Paris Agreement, there will be future global rules that are going to penalize the country for not participating.

I: Yes, like if you want to trade with countries within this group, you will need to pay. And if you don’t have the government tax within your own borders, you will have to pay the group’s tax when you trade with them. It could happen that…[a] special tax [will be added for] those who are not cooperating. I don’t think it’s a good approach to not cooperate with the rest of the world.

A: Going back to priorities, if somebody decides to be a climate activist, let’s put a number between 1 and 10 on the importance of taking CO2 out of the atmosphere, a number on limiting the shorter-lived greenhouse gasses, and a number on emissions reduction. I would give a 10 to taking out CO2, but recently I’m giving the shorter-lived things a very high number, too. But I still give emissions reduction about a 1 at best. What numbers would you give?

I: This is something we maybe don’t agree on. I think [for me] it’s a 10 for short-lived climate gasses, and it’s a 10 for decarbonization as well.

A: Equal.

I: Yes. And pulling CO2 out of the air, also a 10.

A: So they’re all 10. They’re all equal for you.

I: Yes, but we need to figure out what is most important to do right now. Reducing short-lived climate gasses is something we can achieve politically, financially, and practically. CO2 removal is more difficult. I believe that we need to continue decarbonizing. We need to phase out fossil fuel and all that. While we’re doing that, we also do need to remove the [existing] CO2. But the CO2 removal technologies I know of today are scary.

A: Scary because people don’t know about the good way — plankton.

I: The plankton, I need to know more about it. If the plankton really works the way you’re talking about it, maybe we should give that an 11.

A: All right. That’s a beautiful answer.

#2: Oman at a Carbon Crossroads

Dr. Abdullah Al-Abri. Photo courtesy of Petroleum Development Oman.

Here at COP29, activists are advocating for urgent climate action while the fossil fuel industry purports that its role is to sustain global energy needs. We need to make sure that the industry is not denying climate change or obstructing climate progress — as it has for decades — but since we are all in this together, we must find common cause to make sure that we avoid climate ruin. Clearly, collaboration is necessary for solving the climate crisis.

But first, we all need to understand that stopping future emissions — which add about 1% per year to the greenhouse effect blanket — cannot be the only or even the main solution. Activists and governments can then put serious pressure on industry to recognize that the core issue is removing the lethal amount of extra CO2 already in the atmosphere. Only when all parties are focused on the shared goal of removing this excess CO2 and we unite around this worthy and frankly indispensable cause will we succeed. It’s essential for everyone — activists, industries, and policymakers alike — to come together to work toward this critical objective.

It was in that spirit that I interviewed Dr. Abdullah Al-Abri, Oman’s new vice president for sustainability for the Sohar Port and Freezone in the Sultanate of Oman. After working for more than a decade as a petroleum engineer, most recently Al-Abri served as a consultant to the International Energy Agency (IEA) on global energy transitions and strategic investments.

Alex: Please describe this Sohar Port and Freezone. As I understand it, it’s a port meant to facilitate business, and is owned by the government, yes?

Abdullah: Semi-owned. I’m currently working for Sohar Port and Freezone, which is the biggest industrial cluster in Oman and one of the biggest in the Gulf. Obviously, we contribute to the economic, technological, and innovation growth of the region we operate in, but also in terms of the macroeconomics of the Sultanate of Oman we’re very much connected to global trade routes, …playing a central role in stimulating trade partnerships from countries in the west and the east. We’ve got investors [and] companies operating in the Port and Freezone from more than 70 nations. So we’re really vibrant.

We really believe in partnerships. We really believe that businesses have to thrive. And because of that, we are also a firm believer in transition. We’re very much connected to the national, regional, and global dialogues on energy transition. After all, Oman as a country has set a national target for ‘Net Zero by 2050.’ And there is a clear transition roadmap that… all the stakeholders in the country are [following]. And that includes us. So, we need to be net zero by 2050. We are exploring all the pathways possible for us to really achieve net zero. And that includes electrification. That includes efficiency, be it energy efficiency or resource efficiency. That includes hydrogen, renewable hydrogen, low-carbon hydrogen. And that includes (obviously) the CCUS (carbon capture utilization and storage), and circularity and any other solutions that we’re seeing.

AC: Let me back up a second, because ‘Net Zero by 2050’ is a concept that is specifically about future emissions. But right now, today, we have one to two trillion tons of CO2 in the air that we didn’t have before industrialization. That means that if we don’t remove that CO2, soon it will be too hot for people to work outside, too hot for farms to properly produce food, and there will be too much acid in the ocean for fish to even exist. This is where we’re at now, today. But you’re referring to a goal — net zero by 2050 — that’s all over this COP 29, all over the world. You’re certainly not alone in this, you’re with the majority. But today’s CO2 takes a thousand years to go away by itself. So, logically, net zero by 2050 is not really a solution to the climate crisis. Please comment on what really matters for avoiding climate ruin; in other words, what do we do about today’s CO2?

AA: Well, I’m not sure if there is scientifically any magic switch wherein, for example, the world sorts out the tons of CO2 in the atmosphere today.

AC: Yes, but ‘Net Zero by 2050’ is part of the old, false paradigm. The new, better paradigm is to agree that okay, emissions reduction is a fine goal, but it’s not going to solve the problem on its own. The problem is today’s CO2 in the air. How do you remove it? And my question is: Do you have meetings on that? Do you have discussions on that?

AA: We’re placing our piece in the transition puzzle. We remain interested in Oman, [and] are really stimulating innovation in that space — to take out the CO2 that is in the atmosphere today.

AC: Oh, very good. That’s what I wanted to talk about.

AA: And one of the initiatives is, for example, a company in Oman called 44.01 that takes CO2 from the atmosphere and puts it in the ground for mineralization. Oman has certain types of geological rocks that absorb CO2, and then mineralizes [it] for thousands of years. You can see the mineralized CO2 [showing up as] a white kind of color in the stone. So this is something that we are doing to really address the issue today.

AC: Very good. 44.01.

AA: Yes, 44.01 — the molecular weight for carbon. It’s a company established in Oman. It has received a lot of international funding — even, I think, from Elon Musk.

AC: Are you trying to scale it up? Where are you at in terms of the scale?

AA: I cannot speak in detail on their behalf. I believe they’re still in the pilot stage, …but I know the technology can be modular and can be easily standardized. As long as those… geological formations are available, then the technology can be applied. As long as the company receives enough funding from the local and regional stakeholders, and also the international community, I think they would have no issue in expanding and growing.

AC: That’s good. And are you aware of ocean pasture restoration? Through photosynthesis the oceans have the capacity to remove so much CO2 from the atmosphere that we’d be back to a normal greenhouse effect by 2050. It’s called 100 Villages — 100 projects around the world where people are working to restore the nutrition for plankton. Plankton are key. Today they are very far down in health and abundance, but it’s very simple and easy and fast to restore them. This requires restoring their nutrition by tiny amounts — parts per trillion in the water. Oman, facing the Indian Ocean, is an ideal candidate for this geographically.

AA: But it’s not yet applied, right?

AC: It was implemented once in 2012 in the Alaskan/Canadian area of the Pacific. The African Union has put on events promoting it. All over the world, including Africa, it’s starting to come out.

AA: I think you should push such concepts [to] nations like the US, Canada, Europe, and China.

AC: I know that it has been introduced in the Gulf region to certain people. I am curious if you’ve heard about it, this ‘plankton power solution.’

AA: No, no. But we are really deep diving into a spectrum of technologies. In Oman we’re really interested in exploring all the options possible.

AC: Great. Regarding methane and flaring from Oman’s oil installations, there is a new company called CIP, Carbon Investment Partners. They use bacteria to absorb the methane from flaring. Rather than converting the methane to CO2 as in flaring, you don’t create any CO2 at all. It just creates good things that you can use for food, proteins, and biodegradable plastics. Have you heard of this?

AA: I might have, at some stage. But we have solutions today. We have renewables (everybody is doing renewables), electrification. We’ve got energy efficiency that is already in practice. We’ve got the CCUS that’s already been piloted, and as we speak, in Oman and Saudi Arabia we’ve got many… a spectrum of solutions.

AC: Yes, these things do help. But because we want to get beyond these conflicts here at COP that I think are counterproductive, I want to make a list of all the things you’re doing that can remove CO2 and really avoid climate ruin.

AA: Yes, if there is any interest from these companies or beyond to really pilot or test anything in Oman, I’ll be keen to see the potential, see the prospects.

AC: Innovative ideas.

AA: Innovative ideas. Yes. And if the potential proves really promising, then I don’t see any reason for it not to scale up.

AC: Good. Now, would you like to clarify anything? Because, you know, when you walk around this conference there are many people claiming that they’re against oil companies. Do you want to make any statement on that?

AA: One of the top agendas for almost any country in the world, I presume, is to really drive economic and technological growth, right? So that’s without a doubt. And that applies to Oman, [too], of course. And for us, that still remains a top priority. We need to do economic development, technological development, innovation, and [strive for] prosperity… for society — that’s top [on the] agenda. And, you know, for us to do it… now and in the future, we just need to be a lot more environmentally cautious, a lot more innovative, a lot more open. We’ve been open to partnerships of all sorts, whether it’s technological partnerships, investment partnerships, or even market sharing or market creation partnerships. We’re very open. We’re willing to push the boundaries even further on this because we need those collaborative solutions. We are facing a crisis that, as you’ve said, has already been accumulating for years, for decades. And we need that fast-paced and collaborative [approach].

AC: What are the biggest questions in Oman about how to move forward? Is there a particular issue that’s being discussed?

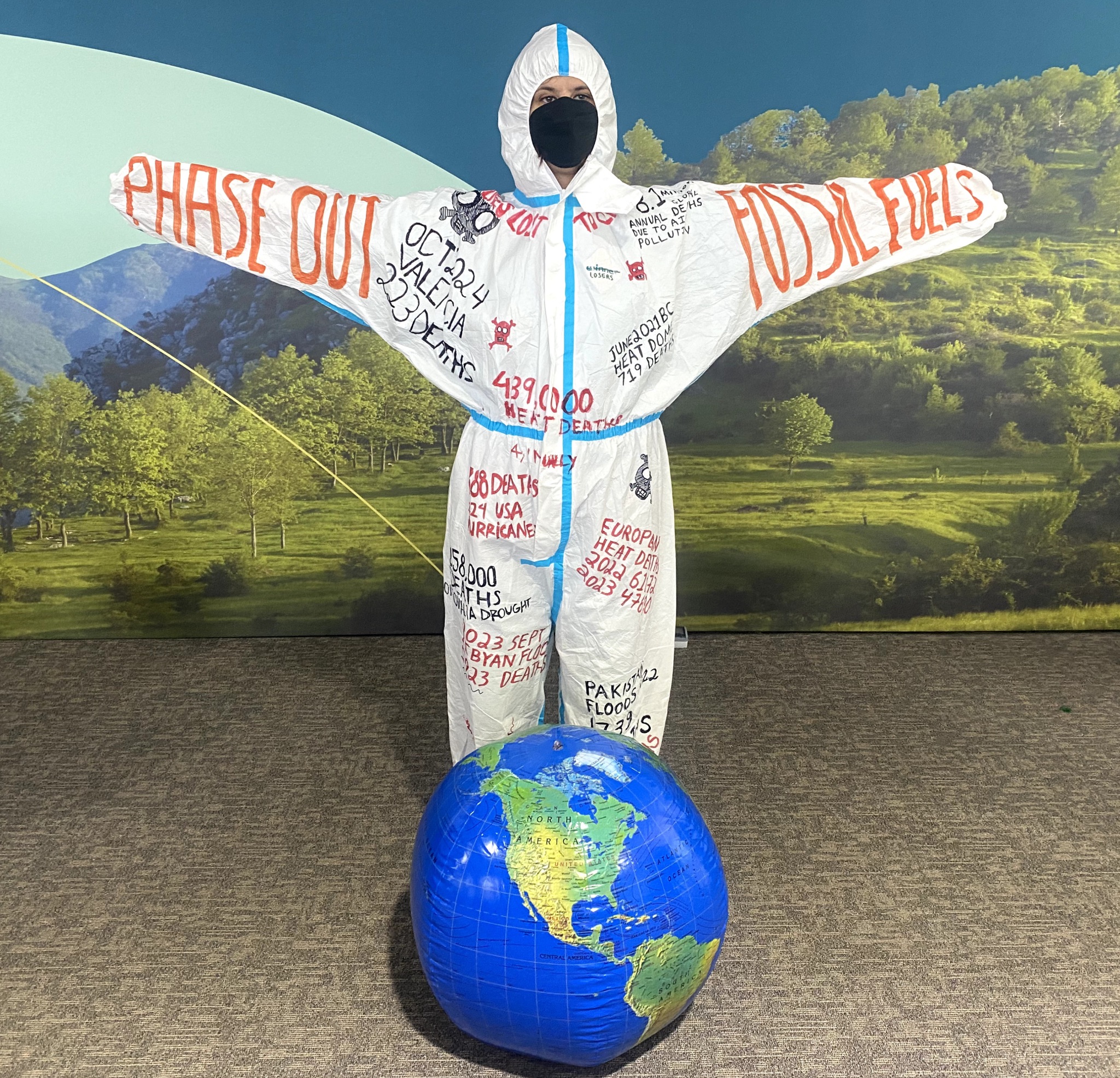

Activist at COP29. Photo by Alex Carlin.

AA: We are convinced that we need to play our role in this global transition agenda [even though] Oman is, after all, a really tiny, tiny, tiny emitter on a global scale. In comparison to the US, Canada, Europe, China, or India, we’re nothing. Yet, we’re still serious. We’re still open. We’re still looking for opportunities. We’ve got a net zero target by 2050. We’ve got a lot of natural resources that we try to tap into, like, for example, solar, wind, geothermal, and those strategic storage locations for the CO2, as we just described. We’re exploring every opportunity, obviously, in the best interest of Oman at large, but also of the global community. We’ve been [adhering] to the best possible international standards. We continue to have dialogues with advanced nations for technological partnerships, for innovations, for financing, for setting standards, for setting up new international trade corridors… for clean products, for clean fuels. We’re very active in this space. So, yeah, we’re open, and we will continue to be so.

AC: One last question. People are criticizing Azerbaijan’s hosting role here, saying it is a “petrostate” and therefore it’s just trying to exploit or corrupt the process. Can you respond to that? Will you please help clear the air so we can all work together?

AA: So, indeed, hydrocarbon products have contributed so much to the growth of humanity over the last decades. And now, speaking about petrostates, those states that are producing big volumes of oil, you know we could say the Gulf states, Australia, the US, Canada — they’re all producing big volumes of hydrocarbons. Let’s say they all agree to stop [producing] oil and gas today. The whole world would stop rotating, so to speak. It’s not really a solution.

AC: Well, if you closed down all the oil companies right now, we’d still be facing essentially the same greenhouse effect.

AA: The effect is there. And we would create huge social unrest because they employ a lot of people in the US, Canada, the Gulf, and Australia. Whether it’s the production of hydrocarbons or the refining and the downstream of the energy sources as central parts of the economy, big percentages of the economy are involved with this. So there isn’t really an easy solution. I think hydrocarbons — and this is according to the IEA and IRENA [International Renewable Energy Agency] — they still see oil and gas playing a role through 2050. So, until 2050, the world will still need oil. The world will still need gas, according to those international organizations. It’s just that we need to make it cleaner. We address the global effects by addressing the various solutions that we’ve discussed. We still need energy. We still need hydrocarbons for our industries, for our applications, for our mobility, for the things that we do day to day.

AC: But I was talking about removing CO2 and you’re talking about future CO2 emissions and offsetting.

AA: Indeed, we need to look for solutions that offset and also address those accumulated emissions in the atmosphere. And I believe that here the big industrial nations really have to step up, because, you know, talking about morality, talking ethically about past emissions, about taking out what’s in the air…

AC: … they need to clean up their mess.

AA: Cleaning up the mess, indeed. And they need to step up innovation and the application of technologies. And indeed, the mess that was created in the first place has to be cleaned up. Somebody has to take care of it [and also] the emissions in the future….

Make no mistake, if we stick with the current paradigm of believing that “emissions reduction” is the main solution, we will end up with climate ruin — in a world that is too hot for people to work outside, too hot for farms to properly produce food, and with too much acid in the ocean for fish to survive. The time is now to implement a new paradigm featuring CO2 removal, methane reduction, and nature restoration. Why? Because, frankly, time is up. It’s now or never. We can’t afford any more delays due to a false mantra. Let’s push Dr. Abri and other representatives of the fossil fuel industry to marshal their immense resources and combine forces with climate activists to act on real solutions to the problems that brought us all together here for COP29.

The fossil fuel industry could easily finance global CO2 removal projects — including the restoration of the oceans, which will sufficiently reduce the greenhouse effect and ocean acidification — while also paying for comprehensive reductions of methane. By doing so, the industry would clean up its mess and give the world a healthy environment without ruinous heat and deadly ocean acidity. This should be the basis for a new social contract between the fossil fuel industry and society at large.

#1: Curbing Non-CO2 Climate Menaces

Zerin Osho. Photo by Alex Carlin.

Arriving at COP29, the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Baku, Azerbaijan, we were greeted with remarks from Simon Stiell, executive secretary of UN Climate Change, who delivered this opening salvo:

“If at least two thirds of the world’s nations cannot afford to cut emissions quickly, then every nation pays a brutal price.”

We will certainly pay an extremely brutal price if we equate cutting emissions with an actual “climate solution,” because cutting emissions only prevents a 1% annual increase in the main problem: today’s lethal level of atmospheric CO2. Sadly, the COP29 leadership is missing the point and still framing the main problem as ‘if we just stop the cars and oil companies from emitting so much CO2 then we will be fine,’ which ignores the fact that even if cars and oil companies were to vanish instantly, we would still face virtually the same disaster.

As the Royal Society, the UK’s scientific academy, points out, “Even if emissions of greenhouse gasses were to suddenly stop, Earth’s surface temperature would require thousands of years to cool and return to the level in the pre-industrial era.” This is mainly because atmospheric CO2 takes centuries to go away by itself.

Fortunately, there are good people here at COP29 who are pushing for solutions that involve the obvious necessity of removing already existing greenhouse gasses. And CO2 is not the only greenhouse gas that needs attention.

Here at COP29, I had a conversation with Zerin Osho, director of the India Program at the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development based in Washington, D.C., about the critical need to address methane and other types of emissions that trap even more heat than carbon dioxide does.

Zerin: We have two buckets of greenhouse gasses and pollutants. There is the carbon dioxide bucket and then there is a non-carbon dioxide bucket. The differentiation is based on their lifetimes in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide has a 100-year lifetime — there are remnants of the gas that is present in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. And then there is a second bucket or clubbing, which is non-carbon dioxide. They’re clubbed differently because they have shorter lifetimes in the atmosphere. So, you have methane, you have nitrous oxide, you have HFCs [hydrofluorocarbons], and you have sulfur dioxide, which is black soot, or “black carbon.”

Now, when we look at what the governments all over the world have done for their “nationally determined contributions” under the Paris Agreement, all of the focus has been on carbon dioxide. But let’s look at it in terms of global warming potential. That is, if you emitted one ton of carbon dioxide, what is the heat trapping ability of it? Let’s call its heat entrapment potential “one.” But non-CO2 gasses and pollutants have several thousands of times more potency for heat entrapment. For example, black carbon — black soot — entraps 50 to 60 thousand times more heat.

Alex: Wow.

Z: Yes. Methane entraps 80 times more than CO2, but that is on a 20-year time scale. Now, the only thing that was developed — by choice or by design or by destiny or who knows why — was the science on CO2. All of the focus so far has been on reducing carbon dioxide as the emission.

A: Yes, CO2 — and only on future emissions, ignoring any removal of current CO2.

Z: Exactly. Only future emissions, nothing to do with what’s there now. Absolutely. So, when you are only looking at CO2, and on those long-term, large-scale time horizons, what’s happened is that we have forgotten a very important piece of the puzzle, which is the non-CO2 substances that trap heat. There’s no spotlight on them. And the summer months in the global south are getting extremely hot. Now in India, for example, in the national capital in Delhi, we faced 50° Centigrade, which is 125° Fahrenheit.

A: Right. So, can you describe how important the methane and the non-CO2 materials are for this jump in heat to 50° C? In other words, how many degrees is the temperature going up because of CO2 compared to non-CO2 materials?

Z: It’s about 50/50.

A: For you and your movement to reduce non-CO2 materials, is there an analogy to the “plankton restoration” success scenario that claims to be able to restore atmospheric CO2 concentrations to safe levels by 2050? What is your timeframe? Can you claim to deliver a decent future to a 10-year-old kid in Azerbaijan?

Z: If we started today in 2024, we could be looking at a methane reduction of at least up to 50% by 2030.

A: Amazing.

Z: Sure, and non-CO2 materials have really short lifetimes. That means there’s actually no need to invest in removal as [with] CO2. For black carbon, it’s more about emissions.

A: Interesting!

Z: Let’s talk about methane. The largest sources of methane in the world are [the] oil and gas sectors.

A: From when they burn the excess in flares?

Z: Yes flares, but also methane leaks from the pipes. But methane also comes from the waste sector and from growing rice. And there are also… natural sources of methane, but the problem is not the natural sources…. Rather, it’s the frequency and the volume of anthropogenic methane emissions we are adding.

A: Okay, but how much of our emissions are manmade methane compared to natural sources?

Z: We are now just starting to [overtake] natural methane emissions — to produce more than nature — so it’s about 50/50.

A: But we may be facing immense methane burps from when the Arctic permafrost melts and the methane escapes, right?

Z: Yes, yes. And the impact of global warming and climate change on the Arctic is four times that of the rest of the world. You are looking at the equivalent of 25 years of global carbon dioxide emissions if methane gets released from the permafrost.

A: So this is a “natural source of emission” but being released due to anthropogenic reasons.

Z: Yes, it’s human-caused anthropogenic warming, which is leading to the thawing of the permafrost, which then leads to methane emissions. So it’s cyclical.

A: So what are you coming here to say at COP29? What is your action plan?

Z: We look at the top three emitters of non-CO2. It’s the United States, China, and India. The United States, even under the Democratic Party, is [emitting] methane, methane, methane. The United States’ largest methane emissions come from oil and gas.

A; Are they flaring?

Z: Yes, they flare, and there are pipe leakages. The pipes for LNG and gas have huge leak rates. And there’s very little data on it.

We have just witnessed the US election. Unfortunately, in the US, you have[now] got President-elect Trump, and there’s so much chatter around the room about what a Trump presidency means for climate. But let’s take a few steps back. You also look at what the Democrats did in the White House. They [daily] produced 30 million barrels of oil and gas — [an all-time high and more than any other country in the world] — under President Joe Biden. The second thing is, while America steadily increases oil and gas production, it also pitched to the world something called the Global Methane Pledge.

A: The Global Methane Pledge? They signed something?

Z: No, no, they didn’t sign [any]thing. They said, “we will sign it along with Europe,” so they co-led it along with Europe — the EU — and went to the world and said, “please sign the Global Methane Pledge,” which reduces methane emissions by 20 or 30%. So, they went to the global world — basically developing countries all over the world — to say, “join the pledge.” But, when you join the pledge, where are the emissions [in] the Global South coming from? It’s the waste sector and it’s rice paddies. But rice is the survival staple meal for more than 2 billion people.

A: You’re saying it’s unfair. We are making them sacrifice too much.

Z: Exactly. And all the while [the US keeps] on producing 30 million barrels of oil, and [talks] of a “just transition.”

A: And oil production also creates methane?

Z: Yes, yes, yes. When you drill down through the cores of layers of the earth a lot of methane comes out.

So back to our action plan. In farming you want populations to move away from methane-intensive activities. For example, in the rice paddy fields, instead of the traditional inundation of fields with water, you can start training people to practice “alternate wetting and drying” — AWD.

Rice paddies are key. Photo by Nikhil Kumar.

A: AWD is a different way to make rice without emitting methane?

Z: Correct. So instead of flooding the farm, you water it and then you don’t water it and then you water it. It’s a practice. And how do you convince farmers who’ve been practicing traditional farming techniques over generations to suddenly move to AWD? You do so by creating financial incentives. An example of that is the creation of carbon markets — trading markets where you trade methane credits, which they can convert into money.

In these systems, we convert everything to CO2 equivalents. So, if you have methane you will convert it to “CO2e.” If I’m mitigating, say, 10 units of methane, I have to now look at what that means in [terms of] a CO2 language, right? To convert it, we look at GWP — global warming potential.

Methane traps 80 times more heat than CO2, but lasts only 20 years instead of CO2’s 100 years. We are working to make the conversion more correct, to make the methane market the way it should be — and not the way some people think it should be, but the way it really should be. Currently if CO2 gets one dollar for each unit, methane is only getting 20 cents because of the 20 years versus 100 years. We will be making sure that we multiply that by the 80 times more heat trapping factor. So, it should be 16 dollars per unit because it is 80 times 20 cents.

A: So that is one thing you’re advocating at COP 29. Is there a methane market right now?

Z: No, it does not even exist yet. And the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] also does not have anything. [They are] not even talking about it.

A: Well, we are talking about it.

Z: Yeah, so what we are doing in India is [going] to our agrarian economy states, sub-national states, sub-national governments. And we are helping them create the trading framework to mitigate methane separately from CO2. We want to separate CO2 markets from methane markets because if you do them together it becomes very difficult. It’s confusing. It’s not pretty.

A: What about small farmers versus large farmers?

Z: You don’t need to convince farmers. You do need to convince the governments. Then the money changes people’s minds.

I will give you an example of a company in India. It’s called Mitty Labs. Mitty Labs already has 30,000 hectares of land under AWD.

A: Oh, that’s good. So you’ve got some people working on this already.

Z: Exactly.

A: You’re saying we can get rid of 50% by 2030. How much is the AWD going to account for?

Z: That’s like half of it. Now we know that AWD works. But there are no methodologies that have been finalized on emissions monitoring. There is no consensus on monitoring. There is no consensus on how to observe data. There are no integrated observation systems set up. They have zero data available on it. And it’s AWD plus DSR, direct seeded rice.

A: Direct seeded, that’s another way to avoid methane?

Z: Yeah, exactly. [With] both these technologies (and we have many such technologies) the problem is that there is no data available.

A: So this is in its infancy. Governments should be talking about this.

Z: Exactly. But if you see India’s BUR, the Biannual Update Report to the UNFCCC [UN Framework Convention on Climate Change], you will see that the government of India wants to promote AWD and DSR. They’re bringing it to the table. And we work closely with the Qatar delegation.

A: So, you’re saying that India as a nation is behind your efforts. You and your colleagues have already convinced the government of India?

Z: Absolutely, absolutely. They get it already. The government of India was convinced before we came on the block. We are pushing it.

So the second sector that I want to speak about is the brick kiln sector, and black carbon.

Kiln chimney. Photo by Nikhil Kumar.

A: Brick, like building bricks.

Z: Yeah, yeah. A brick kiln is how they make the bricks, which is done in India and other countries.

A: And people make huge amounts, right?

Z: Yes. And brick kilns are the hotspots of black carbon emissions.

A: All over the world?

Z: All over the world, but a lot of it is in South Asia. So, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, that belt. It’s called the Indo-Gangetic Plain area. That is the global hotspot for black carbon because the volumes are so huge.

A: Black soot.

Z: Yes. Brick kilns and also residential heating and cooking are the other sources of black carbon from that part of the world.

For solutions, when we looked at what philanthropy and general science talk about, they basically promote something called “zigzag.”

Zigzag technology essentially is an improvement over an open pit brick kiln farm. You create fire and you put the bricks in to form them. Now when we looked at the data — and this is in the context of everybody slapping the government of India left, right, and center about not doing too well on zigzag technology and [asking], “Why are we not adopting zigzag technology?” — it was touted as [a] silver bullet.

A: Okay.

Z: However, we got the data from three large Indo-Gangetic states in India. They are 100% zigzag technology. But, it didn’t work! It did not reduce the black soot. The reason for that is everybody forgot to explain to them how to properly do the implementation of the zigzag technology. How to do it correctly. And then the second problem with that was monitoring. Many people have found problems in the continuous emissions monitoring systems… commonly used to look at these emissions. And nobody is really putting down the standard operating procedures on how to monitor emissions from brick kilns, and how to reduce emissions from brick kilns. Does it work? Does it not work?

And now there is another technology that is being touted as [a] silver bullet, which is called the “Hoffman” or “Tunnel.” Tunnel and Hoffman are the new generation, which is [an] improvement over zigzag. They reduce your black carbon emissions to zero.

A: So now you want to go from zigzag to Tunnel?

Z: There’s a lot of pressure on governments to move. There’s a lot of pressure on the government of India to move all of our existing zigzag kilns to Tunnel and Hoffman. But the amount of CO2 emissions they produce do not justify their adoption.

A: You mean they create extra CO2?

Z: Yeah, a lot of it and also it is super expensive.

A: So what’s the real answer?

Z: The real answer is implementation capability and capacity building. The people who made zigzag were never trained on how to make zigzag work.

A: So you’re saying the real answer is not to go to Tunnel and Hoffman.

Z: Yes, let’s go back to zigzag and do it right and properly.

A: How do you do it correctly?

Z: So, for example, the chimneys have to be thick. If you have a thick chimney, black carbon emissions are reduced. But higher temperatures have to be reached. When you have really high temperatures, black carbon emissions are reduced. But it’s a double-edged sword because when you want really high temperatures you need to use fuels with very high calorific value, which is most likely going to be fossil fuels.

A: So how do you resolve the problem?

Z: Thicker chimneys and better monitoring systems. Together, that can create a solid zigzag. You also make a black carbon unit in a carbon reduction market like I was talking about with methane, but you do it for black carbon on a very small scale. And you start including the cement industry so that you start pumping money into the brick kiln sector as a whole. And then you start slowly moving to a finer sophisticated technology that is very expensive right now.

A: Zerin, have you heard about the technology that uses bacteria to solve the methane problem?

Z: Yes, this is basically biology, right? There are some bacteria like methanotrophs that are able to convert methane. They are able to change the composition when they ingest methane, when they consume methane and turn it into different types of products. So it’s a biological process. I have yet to see commercialization of this technology, and I am not aware of the commercial aspects, the actual cost. It is competitive, perhaps?

A: Yes, I know about a company doing that called CIP, Carbon Investment Partners. They use methanotrophic bacteria to absorb methane. They produce single-cell protein for animal feed and even for some human food. The process can also be used to create biodegradable plastics. And about those flares from the oil companies. They take flare gas in and release only clean, natural air, single-cell proteins, and biodegradable plastics. Are you interested in this as part of your tool kit? Would you include this in your suggestions to the Indian government?

Z: If this works, then of course.

A: Especially with the fact that it doesn’t create CO2 when it absorbs the flares. Do you approve of this?

Z: Yes, totally, totally, yeah. Yeah perfect, that’s wonderful.

And lo, and behold, as we were speaking, the US was issuing this strong buttress of support: “Not only are these non-CO2 super pollutants causing over half of today’s climate change, they are also the fastest way to cooling the planet,” said Rick Duke, deputy special envoy for climate at the US Department of State.

Sign up for our biweekly newsletter to stay updated with our latest work!

Take a look at the philosophy of this conference : Quoting a facilitator who created a board game to plan out a credit market, ““I want most people to lose, but to blame themselves.”

If the UN were serious about a cooperative effort then they wouldn’t have selected a problem solving game designed to make people blame themselves personally for systemic issues.

The combination of idealism, that you can hope and think your way out of material political issues, with the corporate dogma that the bottom line comes before any admission of responsibility, is clearly still in the Kool aid.

https://apnews.com/article/climate-change-board-game-disasters-simulation-3d7e8a21305f448b40c836df010f6241

What a great interview. I had no idea that methane was such a big player at this point and no idea that farming techniques were driving emissions. I really think this article should be reprinted in WAPO or NYT. It’s really important.